On a ridge overlooking a fertile valley, the farm Onverwacht, on 4 th January, 1902 the advance guard of a British column settled down for a midday meal. The commander of the detachment, 110 men of the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen together with a company of mounted infantry of the Hampshire Regiment and some Imperial Yeomanry, was Major John Maximilien Vallentin of the Somerset Light Infantry. Major Vallentin had been in South Africa since before the war and was Brigade Major in Ladysmith when hostilities began. He had enjoyed a varied career in South Africa , behaving with “conspicuous gallantry” at Elandslaagte on 20 th October, 1899 and later, while inside Ladysmith serving as A.D.C. to Brigadier General Ian Hamilton. He contracted enteric fever but recovered to rejoin Hamilton later in 1900 in Bloemfontein . Then as Commissioner of Heidelberg he lived with a Boer commando in that neighbourhood for a week while Field Marshall Lord Roberts’ Proclamation was under discussion. He was four times mentioned in dispatches and described in the “Times History” as an “officer of proven gallantry and capacity”.

Vallentin had halted his men on a flat area on the summit of the Bankkop range of hills, thirty kilometres east of Ermelo. Pans, small depressions where water collects since the underlying strata does not allow it to drain away, provided some refreshment for the horses and the men and so they off-saddled and prepared a meal. In order to protect against surprise, Vallentin placed pickets along the ridge running a few hundred metres to their front in a line stretching about three kilometres. This was a very strong position; secure from attack in front by the steep ridge while behind them were the soldiers of the Hampshire Regiment and the rest of the 19th Company of Imperial Yeomanry, Scots from the Lothian and Berwickshire. Attack from behind across the flat ground was highly improbable therefore. Not far away, in the direction of Ermelo was the column of Brigadier General Herbert Plumer, nearly a thousand men with mounted infantry and artillery. Even closer, to the east of them, was another column commanded by Scots Guardsman Colonel William Pulteney with a similar complement.

Brig General HC Plummer CB ADC |

Major F.W. Toll |

Major J.M Vallentin |

For a month now eight British columns under the energetic leadership of Major General Bruce Hamilton had been searching for General Louis Botha who was known to be in the area with a force of about 700 men. Botha had been leading something of a charmed existence of late, coming close to capture on the 4th December, 1901 when Colonel Sir Henry Rawlinson raided the farm Oshoek at dawn and captured more than a hundred Boers, wagons and supplies. Botha’s men were driven eastwards and Plumer and Pulteney made contact again at Kalkoenskraal on 6th December but Botha once again evaded capture.

The British now knew Botha to be somewhere along the upper Vaal River , a well-watered area of hills and ravines and the search for Botha’s force now intensified. Hamilton and four columns were to the east of Ermelo. Two more columns moved south from Carolina and a number of small laagers were successfully raided during December. However, General Coen Brits managed to ambush part of Brigadier General J. Spens’s column on the farm Holland on 19 th December and inflict 140 casualties, most of them captured. 4 Brits evaded encirclement a few days later as three columns, Plumer, Pulteney and Spens, closed in on him and on 26 th December he joined up with Botha.

On 1st January 1902 the three British columns headed south east out of Ermelo. Spens returned to Begin-der-Lyn to guard the blockhouse line between Ermelo and Standerton while Plumer and Pulteney moved along the Piet Retief road. On the night of 2nd January the two columns, more than two thousand men with guns and transport, camped on the farm Maviristad, uncertain of the precise whereabouts of their enemy. That night the Boer force was not far away, camped on the farm Windhoek owned by the widow Ernst, whose husband had been killed early in the war in the fighting along the Tugela River.

The next morning patrols were sent out into the hilly surrounding countryside, its kloofs and gullies affording ideal hiding places for the Boer commando. One of the patrols comprised of men of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, was surprised and surrounded by Boers from General Opperman’s commando on the farm Rotterdam . Twenty-eight of them were captured, disarmed and released. It is said that Opperman gave their officer a horse to make his way back to the camp at Maviristad. Another patrol was attacked that day on the farm Vlakfontein, along the Vaal River, and five of their number were cornered in a kraal and forced to surrender. The intelligence gained from these two incidents gave Plumer a clear indication of where Botha’s force might be hiding. On the morning of the 4th January Plumer’s column marched north along the Vaal River while Pulteney followed the lower road that would take him past the farms Waaihoek and Vlakplaas and onto the eastern edge of the Bankkop range of hills. The intention was to encircle the Boers in the Bankkop hills.

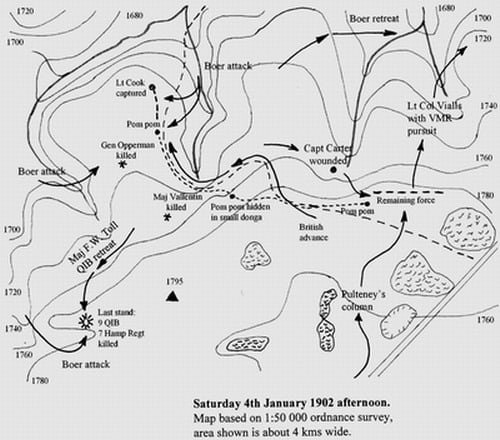

The events of the 4th January have been well documented. The letter of a young private of the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen, David William Priest, to his father and brother also has a sketch map. This, as far as is known, is the only diagram of the action in existence. Exploration of the site turns up a number of the features described on Priest’s map and this has proved to be the key to understanding what happened that day. Priest states in his letter that they “moved off at 5 a.m. with light transport and guns only. QIB’s advance guard on left and Pulteney’s corps on the right about 6 miles from us, snipers were shooting at us all morning. No one hit.” Clearly the Boers were watching the advance closely, but not too closely if they could not hit anyone all morning.

The Boers had slept that night on the farm Schimmelhoek where there is a sheltered kloof. Five or six hundred horsemen and their mounts were easily accommodated. In the morning General Botha told Brits, Opperman and Chris Botha that he had received information that the advance guard of a British column was approaching and he advised withdrawal. His generals were not in favour and advocated a strike against the enemy. In true Boer democratic fashion the three juniors prevailed over their commander and Brits planned the attack and the placing of the commandos. They were from Wakkerstroom (Chris Botha), Swaziland (Koot Opperman), Standerton (Brits) and Ermelo (Commandant Bosman). Brits, as the originator of the plan would be in field command.

The trap was carefully planned and as Vallentin’s force arranged their pickets along the ridge, General Brits deployed the Boer force. About 500 of the men were hidden in a kloof which today has been dammed and stocked with fish. In another ravine to the south east was another force with yet another body of Boers hidden in another fold in the ground further to the south east. Below the ridge where the British pickets were watching for any sign of Botha’s force was a flat shelf about a kilometre square. There were ravines on two sides and the western edge dipped down to the small river running north westwards to join up eventually with the Vaal River .

Major Fred Toll led his men up this slope (the monument is just behind the photographer) and attempted to hold the exposed position at the summit. More Boers, hidden in the ravine to the front managed to advance from the left and enfilade the position.

Major Fred Toll led his men up this slope (the monument is just behind the photographer) and attempted to hold the exposed position at the summit. More Boers, hidden in the ravine to the front managed to advance from the left and enfilade the position.

View from the top of the ridge. Major Vallentin’s patrol came down the ridge along a roadway to the right of the trees in the foreground. They advanced in line over the flat area towards the small bushes at right centre where they had seen fifty cattle disappearing out of sight towards the stream that runs along the valley. The main Boer force attacked from the ravine on the right and attempted to capture the British pom pom which was withdrawn back up the ridge and hidden in a small donga on the slope.

View from the top of the ridge. Major Vallentin’s patrol came down the ridge along a roadway to the right of the trees in the foreground. They advanced in line over the flat area towards the small bushes at right centre where they had seen fifty cattle disappearing out of sight towards the stream that runs along the valley. The main Boer force attacked from the ravine on the right and attempted to capture the British pom pom which was withdrawn back up the ridge and hidden in a small donga on the slope.

A decoy was arranged, fifty cattle with a few Boers to herd them along the flat ground and down over the rim towards the stream. The Boers in the kloofs were out of sight of the Queensland men on the ridge but the decoy was spotted and reported to Major Vallentin who determined to investigate. Leaving some of the men on the ridge in a secure position, the rest headed off down a roadway leading over the ridge and down onto the lower level. (David Priest’s sketch clearly shows the road which can clearly be identified today although now disused – a pom pom gun mounted on artillery wheels and with horses to draw it could not just be dragged over the veld, some kind of road or track was needed). The decoy had disappeared over the edge of the plateau a bit more than a kilometre away and Vallentin’s force chased after them with the Yeomanry as the advanced screen. The Queenslanders followed with orders to support the Yeomanry. Suddenly from the right flank the Boers opened fire and emerged from the ravine where they had been hiding. They made for the pom pom but Lieutenant Reese of the Q.I.B. was ordered to dismount his men and form a defensive line. They opened fire with the pom pom but it jammed after firing only five shots. Lieutenant H.R. Johnstone of the Yeomanry was shot and Major Vallentin was hit as they tried to get the pom pom away. Two of the gun horses were shot but Q.I.B. Sergeant Major Frank Knyvett rallied the men in its defence (apparently including Private David Priest) and the gun was dragged back up the road and hidden in a small donga.

Major F.W. Toll of the Q.I.B. was now the senior officer present and he managed to organise a defensive line and send some of the horses back up the ridge. A group of men on the left flank under Lieutenant B.W. Cook were taken prisoner but the rest of the force was pushed back up the ridge to a spur on the north east. The Boers heavily outnumbered the Queenslanders and the few Yeomanry as well as some of the men of the Hampshire Regiment, the rearguard who had arrived to assist. On the right some of the Q.I.B., among them the wounded Captain Carter and Lieutenant Higginson, managed to retire up the ridge and join those of the force who had remained on the right of the picket line. A galloper was sent to summon the columns and Colonel W.R. Pulteney’s column on Bankkop to the east was closer than Plumer’s who had followed the line of the Vaal River.

Major Toll and his men were now cut off from the rest of the force. The Hampshires had left their horses in a little hollow behind the spur but the Boers managed to work their way around and attack from the rear. There was absolutely no cover and nine of the Bushmen and eight of the Hampshires were killed before the Boers managed to get in so close that further resistance was suicidal. On the Boer side the loss was heavy and the attacks were pressed home with great bravery and even desperation. They certainly knew that they had little time before more than two thousand men from the two British columns appeared on the field.

General Koot Opperman was killed, shot in the forehead as he urged his men forward. His body lay on the field and the General’s Adjutant, M.W. Coetzer and Willem Collins battled to load the 120 kg body onto a horse. The British columns were now arriving on the top of the ridge and the Boers were now subject to artillery fire. In spite of all their efforts they failed to recover the body which was left on the field although Opperman now lies buried in Vryheid cemetery. Another casualty was the young Mosie Van Buuren who was in charge of Louis Botha’s young son. Shot in the stomach he died later in the day and is buried on the nearby farm Mooiplaas. During the last assault on the spur, Field Cornet Manie Swart complained to General Brits that they could not shoot at the English because they could not see over the edge of the ridge. Brits ordered them to throw stones over the ridge to make the enemy keep their heads down. The Boers then were able to climb over the ridge and jumped right in to the few remaining British soldiers. The Boers had captured thirty unwounded horses but very few rifles and little ammunition for the Queenslanders and the British had hurled their weapons into the long grass and there was no time to search for them.

Sergeant-Major Weston of the Hampshires was wounded, fatally as it turned out, hit by a bullet coming over his shoulder striking his bandolier and bursting two or three cartridges. Taken to hospital in Charlestown , he died there on 22nd January. Louis Botha himself was on the field and although he allowed no looting he asked the wounded Hampshire Regiment’s Captain Leigh for his binoculars. Apparently he was much amused to discover that they had been smashed by a bullet.

Boer casualties were heavy and almost certainly more than the twenty-three killed on the British side (one Imperial Yeoman officer, eight Hampshire Regiment and thirteen Queenslanders as well as Major John Vallentin, their commander). Only five Boers were named as casualties. Jackson states that Sergeant Major Weston told him that the British prisoners, some seventy-nine of them, were used as a burial party and to get the wounded away, “a favourite game of theirs”. Priest too tells how the Boer doctor whose offer of assistance was refused by the British said the Boers had forty-seven killed and sixty-eight wounded.

By now the balance of Vallentin’s force, perhaps forty Queensland Imperial Bushmen, together with a number of Hampshire Regiment some distance away from where Major Toll and the few survivors were captured, had rescued the pom pom from the donga. They unjammed it and opened fire on the Boers now retreating down the valley towards the farmhouse of Onverwacht. The leading elements of Pulteney’s column had arrived on the scene having ridden in from the east over the Bankkop hills. The Boers charged the Queenslanders once again but were driven away by Pulteney’s Victorian Mounted Rifles under Major Vialls. Shortly after, Brigadier General H. Plumer and Lieutenant Colonel F. Colvin and the remainder of the columns arrived from east and west.

Lieutenant Colonel Vialls with the Victorians and other mounted men was ordered to give chase but the Boers had scattered in various directions. Viall’s men made contact some four kilometres away, were charged by the Boers but easily drove them off. Some of the Boers headed for the Vaal River and headed off to the north where they spent the next day on the farm Smitfield, not to be disturbed by the British (who probably had no idea they were there). Jan Moerdyk’s diary for Sunday 5th January says that “after the punishment meted out to them yesterday the enemy left us in peace today” which seems to epitomise the indomitable Boer spirit for their cause which was now clearly hopeless.

During the month of January, the British under Bruce Hamilton continued with their night-raiding tactics but Lord Kitchener’s focus was now shifting to efforts to capture Christian de Wet in the eastern Orange Free State and deal with Koos de la Rey in the western Transvaal . Columns were reorganised and manpower reduced. Louis Botha remained in the area but soon realised that the denuded landscape with the few farms still standing was not able to adequately support his force. The British recognised that to surround and capture him was not even to be attempted. In mid-February Botha and his followers by-passed the Wakkerstroom-Piet Retief blockhouse line by marching through Swaziland and headed into the mountains around Vryheid. Brits went back to the Standerton area and his base at Bloukop. Onverwacht was the last aggressive action of Botha’s commando in the eastern Transvaal and they remained at large in the Vryheid area until the commencement of peace negotiations in April 1902.

After the battle four graves were dug on the ground near the spur – eleven men of the Q.I.B in one, seven from the Hampshire Regiment in the second, five Boers in the third and the fourth for Major Vallentin. Some years later Vallentin’s family arranged for a monument to be erected over the grave which was organised for the family by Captain Siemssen, one of General Louis Botha’s personal staff. In 1962 the bodies were moved from the mass graves on the Onverwacht spur and re-interred in a Garden of Remembrance in Ermelo Cemetery on Saturday, 5 th May. Monuments that been erected over the original graves were also moved and now stand in Ermelo. Members of Major Vallentin’s family and a representative from the Australians were present at the reinterment ceremony.

The monument on the site of the last stand  erected by the local inhabitants on the occasion of the centenary of the action in 2002. The Australian 2/14 Light Horse Regiment unveiled a plaque on that occasion with the names of the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen casualties. Five Boer names are on another plaque but only a piece of the original cast iron cross remains to commemorate the Hampshire Regiment and the Imperial Yeomanry dead.

erected by the local inhabitants on the occasion of the centenary of the action in 2002. The Australian 2/14 Light Horse Regiment unveiled a plaque on that occasion with the names of the 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen casualties. Five Boer names are on another plaque but only a piece of the original cast iron cross remains to commemorate the Hampshire Regiment and the Imperial Yeomanry dead.

In February 2002 local people erected an impressive monument on the original grave site made from stone corner posts and with the names of the five Boers who were buried on the field. The 2/14 Australian Light Horse Regiment (QMI) laid an impressive brass plaque with the names of their dead.  Only a fragment of the original cast iron cross with the inscription “For King and Empire” which was erected over the Hampshire Regiment dead remains, cemented into the base of the monument. The monument site is on private land and carefully guarded by the local farmer so vandalism has so far been avoided. It is a fitting memorial to the brave men of both sides who fought it out along the ridge more than a century ago.

Only a fragment of the original cast iron cross with the inscription “For King and Empire” which was erected over the Hampshire Regiment dead remains, cemented into the base of the monument. The monument site is on private land and carefully guarded by the local farmer so vandalism has so far been avoided. It is a fitting memorial to the brave men of both sides who fought it out along the ridge more than a century ago.

Written by R.W.Smith

Courtesy of Lt Col Miles Farmer

Bibliography:

• Pamphlet compiled by Mrs. Gretchen Celleirs and issued on the occasion of the unveiling of the monument at Onverwacht.

• R.L. Wallace “The Australians at the Boer War” The Australian War Memorial, Canberra , 1976.

• “The Times History of the War in South Africa ” Vol v.

• “The South African War Casualty Roll” J.B. Hayward & Son 1982.

• F.P. du P. Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919”.

• “After Pretoria ” Vol IV

• Private David W. Priest 5th Queensland Imperial Bushmen. Letter to his father now in the hands of his son, Bill Priest.

• C.C.Eloff (editor) “Oorlagsdagboekie van H.S. Oosterhagen” Raad vir Geesteswetenskaplike Navorsing, Pretoria , 1976.

• Albert Schmidt “Jacobus Daniel (Koot) Opperman”, article written for the unveiling of the monument on Onverwacht farm in 2002.

• C.G. Stolp article in “Fleur” 1948 quoted in the inauguration pamphlet.

• P.L. Murray “Official Records of the Australian Military Contingents to the War in South Africa ”.

• Murray Cosby Jackson “A Soldier’s Diary” The Royal Hampshire Regiment Museum Trustees 1999 (reprint of 1913 original).

• Jan Leendert Moerdyk’s “Diary of the First War of Independence” translated from High Dutch by his son Pieter Cornelius Moerdyk.

Notes on sources:

• M.G. Dooner “The Last Post” pp 393-394

• “The Times History of the War in South Africa ” Vol v p 456.

• “The Times History of the War in South Africa ” Vol v p 453-454.

• “The Times History of the War in South Africa ” Vol v p 455. See also F.P. du P. Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919” Chapter 20 – “A challenge for an English Officer is accepted.” His colourful account is worth reading and bears comparison with British accounts of the incident who acknowledge it to have been a rout. There is another account of the action in “After Pretoria” p938.

• See “Oorlagsdagboekie van H.S. Oosterhagen” p16.

• Albert Schmidt article.

• Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919” p74 describes this incident and the wounding of an Ermelo man, one Erasmus, who was taken that night to the farm Schimmelhoek. See also “Oorlagsdagboekie van H.S. Oosterhagen” p16.

• Letter to his father, Private David W. Priest 5 th Queensland Imperial Bushmen.

• F.P. du P. Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919” p 74.

• F.P. du P. Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919” p 76.

• Private David Priest’s letter as well as the reports of Major F.W. Toll and Lieutenant J.B. Higginson.

• C.G. Stolp article in “Fleur” 1948.

• F.P. du P. Robbertze “Generaals Coen Brits en Louis Botha 1899-1919” p 77.

• Murray Cosby Jackson “A Soldier’s Diary”. Pp 308-313.

• Jan Leendert Moerdyk’s “Diary of the First War of Independence”

• “The Times History of the War in South Africa ” Vol v p 459-460.