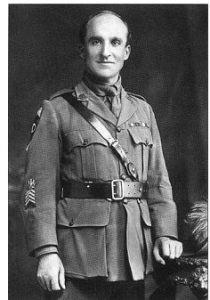

STAFF SERGEANT A.J. COX DCM

4TH LIGHT HORSE REGIMENT (1879 – 1959)

Jack Cox was among the first of the Light Horse Regiments sent as infantry reinforcements to land on Gallipoli on 12 May 1915 as replacements for the number of casualties the Australian infantry battalions had already suffered. Like most of those veterans who did survive Gallipoli, he had many lucky escapes from death.

On one occasion he awoke to find a bundle of 12 sticks of dynamite lying against his head. The sticks of dynamite had been tied together, a fuse inserted and lit and thrown by the Turks from their trenches, which were just a few feet away. It had landed, sometime while he slept, against his head. The fuse had burnt to within one and a half centimetres of igniting the dynamite, but had gone out. Cox had not even woken up when the bundle had landed but he was pretty jumpy when he did.

On one occasion he awoke to find a bundle of 12 sticks of dynamite lying against his head. The sticks of dynamite had been tied together, a fuse inserted and lit and thrown by the Turks from their trenches, which were just a few feet away. It had landed, sometime while he slept, against his head. The fuse had burnt to within one and a half centimetres of igniting the dynamite, but had gone out. Cox had not even woken up when the bundle had landed but he was pretty jumpy when he did.

On another occasion the troops of the Light Horse were ordered to take the Turkish trenches only a few feet in front of them. No thought had been given by higher command that the opposing trenches were heavily fortified, covered with heavy beams and bristling with troops and machine guns.

The Australians were divided into three lines, Cox being the third line. The first two lines had tried to leave their trenches on the command of the whistle blast. They had been chopped to pieces by the ferocity of the firepower and the number of Turkish troops manning the opposing trenches. As the third line was ordered into position not a man hesitated to take his place, stepping between the dead and dying lying on the trench floor. Luckily, before the whistle blast came, the charge was called off.

Cox often said it was impossible to describe the pride of serving with men of such courage. Another night, the Turks attacked the Australian position. As dawn came, the Australians were still holding their line but at a terrible price: reserves had been thrown into the battle until there were none left and although the Turkish dead were thick upon the ground between the opposing trenches, there appeared the possibility that they were preparing to attack again. Cox’s commanding officer made his way forward to inspect the position while waiting for reinforcements to be gathered and sent up. He came to tell his men that they had to hold till then. Cox had his right arm in a roughly made sling because he had been shot through the right shoulder. He was casually lighting homemade bombs from his pipe and throwing them towards the Turkish trenches with his left arm. The colonel ordered him to the regimental aid post on the beach. Cox politely asked the colonel to look through the periscope at the opposing trenches and there the Colonel saw the vastly superior enemy apparently preparing to launch another attack very shortly. He then asked for permission to stay at his post till the reinforcements arrived as there were only 19 men still standing and if he left there would be one less. He recalled how his colonel had stared at him in utter disbelief, quite obviously amazed that Cox was willing to stay there risking his life when he had a chance to leave and be much safer down on the beach.

Cox knew and understood how much his Colonel hated Gallipoli; the constant nearness of death, the fear of movement, the noise of the shells, rifles, machine guns, the flies, the dirt, the heat, the lack of water; and that he couldn’t understand how men lived in the forward trenches with the stench and putridness of decaying flesh. Eventually he gave Cox permission to stay till the reinforcements arrived, when he went down to the RAP and was evacuated to Lemnos, an island nearby, because his wound had become infected.

A couple of nights later, the Colonel recited this tale of heroism in the senior officers’ mess to the senior officer on Gallipoli that night – Major General Cox, commander of the 1st Light Horse Brigade. The General told the Colonel he wanted Cox recommended for a Victoria Cross because it was such men who were holding the peninsula and they deserved to be recognised. The Colonel replied that he could not recall Cox’s name, but that as soon as he could, he would make the recommendation. The lapse of memory lasted for the rest of the war. The conversation in the senior officers’ mess was reported to Cox after he had returned to Gallipoli, by a mate who had been on mess duty that night.

The infection in Cox’s shoulder became worse. He went into a coma and was transferred to the army hospital in Cairo where he lingered between life and death for some time.

Eventually he recovered and returned to Gallipoli. He was still there, now with the rank of armourer sergeant, when the decision to evacuate was made and the brilliant evacuation plan put into practice. His time to leave came in the middle of December, and as he tramped down to the beach to await his turn to be ferried out to the waiting transports, he thought how lucky he was not to have been killed or seriously wounded as so many of his mates had been. The last ANZACs left Gallipoli on 20 December 1915.

In 1916 Cox’s rank was confirmed and he was sent as the senior NCO to help form the Camel Corps, which proved to successful at the Battle of Magdhaba. The capture of this town forced the Turks to abandon the port of El Arish, which is situated approximately where the 90 miles of the Sinai Desert running from the canal ends and where the firm flat lands of the southern Palestine begin. The mounted troops were at last freed from the dunes of deep, loose sand and for the first time in months gained a footing on firm ground. Cox applied for and was granted transfer back to the 4th Light Horse in February 1917. This meant he missed the two battles for Gaza in which the Camel Corps played an important part, but it led to his involvement in the charge at Beersheba.

The defeat of the Turks in Palestine depended on the breaking of their Gaza-Beersheba defensive line. General Sir Edmund Allenby, commander of the British Forces in Palestine from June 1917, carefully prepared his plans. Every effort was made to make the Turk believe the battle would be for Gaza, and it was to this city that Turkish reinforcements were mostly sent. Gaza was known as “the outpost to Africa and the door to Asia”, and its capture was always considered necessary in an invasion of Egypt from the north or an attack on Palestine from the south. Neither the Turkish nor German leaders believed it was possible for Allenby to fling in his chief strength on the Beersheba flank.

While the Turks considered the main attack would be for Gaza, they were nevertheless a clever enemy and had chosen an excellent natural position for the defence of Beersheba, even though the town itself was not really suitable for extended defence. Any troops attacking Beersheba would have to cross country where there was absolutely no cover.

The attack on Beersheba was set for October 31. General Allenby insisted in his orders to his officers that it was imperative to the battle timetable that the town fall on the first day and resistance on the left flank be crushed as soon as possible. Although the water supply to his troops had been earnestly addressed, General Allenby was relying very heavily on the wells at Beersheba to water his troops and horses and if that water was not available by the end of the day he would be in an almost hopeless position.

On the night of the 30th, the mounted troops had a 40 kilometre ride before they could be in position to attack at dawn of the 31st. The infantry were already in their positions. The troops had a full water bottle to last the day; the horses only what their riders could spare from their bottles. There was no reserve. If the battle failed, all troops had the prospect of a two day withdrawal, without water, across a desolate sandy waste.

The bombardment started at 6am. The battle seesawed during the long hot day. Casualties were heavy and although objectives were gained, it was only after very bitter fighting. The timetable was thrown right out, and as the afternoon began to draw in there appeared little chance that the town would fall that day. It was then that General Chauvel, the officer in charge of the Australian Light Horse brigades, decided on one last throw of the dice – a frontal cavalry charge. It was against all odds.

The 4th and 12th Australian Light Horse Regiments had been held in reserve and they were chosen for the charge. The men who had watched the battle all day and had seen the casualties and the tigerish defence of the enemy were eager for action, but the horses had already been 30 hours without water and were beginning to fret. The two regiments were drawn up in three lines. Cox was acting regimental sergeant major at the time and was on the extreme right of the front line. The Light Horse did not carry swords or lances so the troops carried their bayonets in their right hand.

It was half past four when the two regiments moved off on what appeared an impossible task. First at a trot, then they quickly broke into a gallop.

Cox always stated that once the horses smelt the water in the wells at Beersheba it was impossible to hold them. They took the bits in their mouths and galloped all the faster and neither shell nor machine guns nor bullets were going to stop them. British artillery put out of action some of the Turkish machine guns which had started up the “sons of hate” but the Turkish riflemen began rapid fire as soon as the Australian troops came into range. But even their steady shooting could not stop the charging Australians.

As the horsemen got closer, the flustered Turks failed to adjust the sights on their rifles and so the bullets were passing harmlessly over the heads of the Australians. This mistake on their part saved many lives. The Australians jumped the trenches, somehow pulled up their horses and, turning, dismounted and jumped into the trenches. The Turks hated the Australian bayonets and most quickly surrendered or fled. Whereas at 4.30pm the Turks had felt safe behind their defences, felt proud that they had held off the British forces, and appeared to have saved Beersheba and the threat to their line, now one hour later, they were shattered, the town was lost, and their defensive line was wide open. All this thanks to what had appeared a hopeless charge by 800 wild colonial boys.

During the charge Cox saw a Turkish machine gun about to be brought into action on his right. From the moment he saw the machine gun, his reactions almost defy description. In a second he realised that if this machine gun had commenced firing, its enfilade fire would have killed or wounded many of the charging Australians. This could have allowed the Turks with their superior numbers to regain the initiative which could have made a great difference to the result of the battle. It was essential to capture the town that day because of the need for water. If that charge had not succeeded, history might have been different.

Cox’s prowess as a horseman was brought into action the moment he saw the machine gun. Somehow he made his horse, galloping at full speed to get to water, do a right angle turn so he could charge the gun. All he had was a revolver, which he waved at the enemy as he charged towards the, screaming at them in every South African native language he could think of.

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18 Volume II – The AIF in Sinai and Palestine describes his action: “While fighting was proceeding in the trenches, Armourer Staff-Sergeant A.J. Cox saw a machine gun being hurriedly dismounted from a mule by its crew. In a minute it would have been in action at close range. He dashed at the party alone, bluffed them into surrender and took 40 prisoners.”

After the town had been made secure, troops sent forward to harass the enemy, horses watered and fed and the men seen to, Major Rankin, Cox’s squadron commander, told him he had been recommended for a Victoria Cross because his act of bravery had saved a lot of lives. Lieutenant Colonel Bourchier, who was temporary commander of the 4th Light Horse Regiment while its CO was in hospital in Cairo, also advised Cox that he had endorsed the recommendation for his VC and had forwarded it to General Headquarters. He also offered his congratulations and appreciation of his actions in saving so many lives that day. Officers from other Light Horse Regiments came over to congratulate him and Cox sometimes spoke of his difficulty in hiding his embarrassment. One such officer was Lieutenant Colonel Cameron of the 12th Regiment who told him that while he was sorry that Cox wasn’t a member of his regiment, at least the Light Horse were being honoured by one of its members winning this highest award for bravery. He congratulated Cox on his courageous action and thanked him for “saving the lives of a lot of my men.” Cox often spoke of hs very firm handshake which he said he could never forget.

Some weeks later he was ordered to report to the CO who told him that he had been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal, not the Victoria Cross. No reason had been given why his recommendation for the latter medal had been amended. The CO could not understand why the decision had been made. He apologised for raising his hopes and offered his congratulations on his award.

Cox saluted and marched out. He said that he was stunned, and while he had not expected any recognition for his action in the first place, for he considered that he had not done anything braver than a lot of other men, he had been told that his actions deserved a VC and that he had won a VC. Why was his citation changed? He remembered that although the Light Horse had played a major role in capturing the town of Romani early in 1917, very little mention was made of the Australians’ part and very few awards were made to Australians. Were the Australians on the Palestine front overlooked all through the campaign because of an absence of direct touch with the Australian government?

Cox was promoted to warrant officer first class and became Regimental Sergeant Major. He was in action through the fighting in the Jordan Valley. During the summer months the inhabitants leave the valley because the heat is unbearable, but the ANZACs and the Turks fought there for weeks. In one of the actions, he was trying to defend himself from a Turkish attack when a hand grenade landed at his feet. However, it failed to go off. He was also in the attack on Damascus, the last action undertaken by the Australian Light Horse in the 1914-18 war.

Cox came home on the SS Port Darwin which steamed home from Cairo in November 1918 packed with original ANZACs who had been in the first contingent of volunteers to leave from Australia in 1914. He became a soldier settler, a father of six children and a grandfather of 19 grandchildren. He died in 1959, aged 80 years old.

It would be marvellous for the original Light Horsemen, the fourth Light Horse Regiment, and for his family to have his award of a Victoria Cross reinstated posthumously. I have written to Army Records in London but they claim all records have been destroyed by now. There is no doubt his action saved countless lives and perhaps even a battle.

ARTICLE SUPPLIED BY JACK COX’S SON JOHN

| Regimental number | 85 |

| Religion | Church of England |

| Occupation | Assayer |

| Address | Railway Pde, Lithgow, New South Wales |

| Marital status | Single |

| Age at embarkation | 34 |

| Next of kin | Mother, Mrs Mary Cox, Hazelhurst, Hampshire, England |

| Enlistment date | 18 August 1914 |

| Rank on enlistment | Private |

| Unit name | 4th Light Horse Regiment, A Squadron |

| AWM Embarkation Roll number | 10/9/1 |

| Embarkation details | Unit embarked from Melbourne, Victoria, on board Transport A18 Wiltshire on 19 October 1914 |

| Rank from Nominal Roll | Warrant Officer (Class I) |

| Unit from Nominal Roll | 4th Light Horse Regiment |

| Recommendations (Medals and Awards) | Distinguished Conduct Medal

Recommendation date: 1 November 1917

|

| Returned to Australia 15 November 1918 | |

| Medals | Distinguished Conduct Medal

‘For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He, single handed, captured a machine gun with its crew of five men in an enemy redoubt. This gun was the means of holding a strong position, and by his prompt and gallant action, under a very heavy fire, he thus materially assisted in the successful assault upon the objective and saving many lives. His courageous conduct was most exemplary.

Source: ‘Commonwealth Gazette’ No. 110 Date: 25 July 1918 |