The General who defied the British.

Battle of Villers – Bretonneux 25th April 1917

A farm boy who was born near Tiaro, near Gympie, Queensland. With a General’s baton in his crib, became the general who in one night turned the stalemate of the Western Front into the beginning of victory for the Allies in World War One.

A farm boy who was born near Tiaro, near Gympie, Queensland. With a General’s baton in his crib, became the general who in one night turned the stalemate of the Western Front into the beginning of victory for the Allies in World War One.

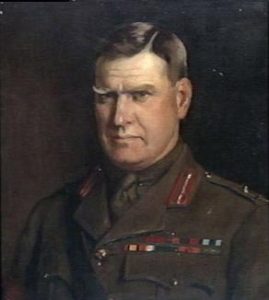

Sir Thomas William Glasgow (1876 – 1955), by George Bell,

courtesy of Australian War Memorial. ART00107

Thomas William Glasgow became the Australian general who stood up to high-ranking British officers to turn potential defeat into brilliant victory at Villers- Bretonneux on Anzac Day, 1918.

It was the Australian’s insistence that the British battle plan for the capture of the French Village was faulty that prevented almost certain defeat for the Allied forces.

“Bill” – later Sir William – Glasgow, born at Blackmount, near Tiaro, in 1876, was just out of Maryborough Grammar School and working as a clerk in the National Bank of Queensland at Gympie when he became a volunteer part-time soldier in the Wide Bay mounted infantry.

He was selected with 19 other Queensland citizen soldiers to attend the diamond jubilee celebrations of Queen Victoria in London and two years later found himself sailing for the Boer War in South Africa as a lieutenant in the Australian Light Horse.

Glasgow distinguished himself in South Africa, being mentioned in dispatches at the relief of Kimberley and returned home with the Distinguished Service Order.

He was a major in the Light Horse unit at Gympie when World War One broke out, and found himself sailing for Egypt as second in command of the AIF 2nd Light Horse Regiment.

The citizen soldier again distinguished himself at Gallipoli, and came out of that campaign as a Lieutenant – Colonel in command of his unit. He was 40 when he was promoted to Brigadier-General and given the job of raising and commanding the 13th Australian Infantry Brigade for service on the Western Front.

The brigade covered itself in glory in some of the toughest battles in France over the next two years. But it was on April 25, 1918, that Glasgow was to write his name into Australian history at the second battle of Villers-Bretonneux, a victory which the Australian senior commander in France, General Sir John Monash, was to call “the turning point of the war.”

Two Australian brigades, Glasgow’s 13th and the 15th under Brigadier General “Pompey” Elliot, were given the job of re-taking Villers-Bretonneux, a French village vital to the integrity of the whole Allied line, after it had been captured from the exhausted British 8th Division the night before. The Germans had ousted the British from the village with an attack led for the first time by tanks, and repeated counter-attacks by the tired British soldiers had failed to retake it.

When the two neighbouring Australian infantry brigades were called in to help, Glasgow went to see the British 8th Division commander, General Heneker, several kilometers away to discuss battle plans. Glasgow decided to go see the potential battleground for himself. Australian World War 1 official historian C.E.W. Bean recounted the story of what happened when he returned.

He told Heneker he had decided to start from a north-south line – said to be clear of the enemy – between the wood and Cachy village and to attack eastwards, south of the wood and past the south of Villers-Bretonneux.

“But you can’t do that” was the reply. “The Corps commander says the attack is to be made from Cachy.”

Glasgow said he could not do it that way.

“Why, it’s against all the teaching of your own army, Sir, to attack across the enemy’s front. They’d get hell from the right.”

Attacking eastwards, he would have his right (flank) protected and could do something to protect his left by dropping troops as he advanced, to deal with the wood.

“Tell us what you want us to do, Sir,” he said, “but you must let us do it our own way.”

It was therefore settled that the attack should be made as he desired.

But Glasgow was not quite finished with Heneker. As he was leaving, he asked the British commander: “What about the time? You must coordinate that, Sir.”

Glasgow proposed that the attack start 10.30pm. But Heneker said that would not do, and wanted to start at 8 pm. Glasgow pointed out that that was only a few minutes after sunset, and the Germans would still have clear enough light to see the Australian troops massing at their start lines.

Heneker again mentioned the Corps commander, who he said, “wanted it done at 8”.

Glasgow exploded. “If it was God Almighty who gave the order, we couldn’t do it in daylight,” he told the British officer.

Heneker said all the other troops would be ready at 8 o’clock. After Glasgow had been asked successively by the Corps commander, General Butler, whether 8.30, 9, or 9.30 would suit him, he eventually compromised on 10 o’clock.

The ensuing attack on the Germans was a resounding success.

Bean was to write in the official Australian history of World War One:

“Before sunrise, this bold, clean stroke . . . had rescued the Allies from the anxious situation existing at sunset.

The swiftness and finality it imposed upon a critical and peculiarly bloody action – for on the narrow British front alone there occurred more than 20,000 casualties, British and German – and the success attained in spite of the flouting of some of the usual rules for such operations have caused it to be not infrequently cited as the most impressive operation of its kind that occurred on the Western Front.

There exists ample evidence of the impression made on the General-in-Chief of the Allies.

Speaking after the unveiling of a memorial to Australian soldiers in Miens 18 months later, (General) Foch referred to their “altogether astounding valiance” in this counter-attack.

“The high command, he said, had merely the task of living up to the standard imposed by such soldiers.”

Bean says that without Glasgow’s interventions the start would have been made too early.

“It was rugged determination of Brigadier-General Glasgow that saved the army and corps commanders and everyone else concerned from what would have been the tragic mistake of launching the attack . . . at 8 o’clock, when there was still a full hour’s twilight and the enemy could not have failed to received not only good warning of the assembly of troops but news of their progress during the attack,” he wrote.

“Even as it was, scouts going forward to lay the (startline) tape were seen by the Germans. Had Glasgow insisted upon his own proposal to attack at 10.30, the success of the operation would probably have been greater than it was.

Without Glasgow’s strength holding his point against the pressure of an hierarchy of commanders, the effort would have been futile”, according to Bean.

The soldier boy form Tiaro was promoted to Major General and given command of the Australian 1st Division.

He returned to Australia and left the AIF exactly five years to the day after he enlisted.

In 1919, Glasgow was knighted and went back to the land, raising cattle in central Queensland.

He went into Federal Parliament as a Senator in 1920, and served as Minister for Home Affairs and Minister for Defence.

In 1940, Sir William became Australia’s first High Commissioner to Canada, and served in that office until 1945. He died in 1955.

Published with the kind permission of The Courier Mail.

Hon. Sir William Glasgow was the Founding President of

The Society of St Andrew of Scotland (Qld) in 1947.