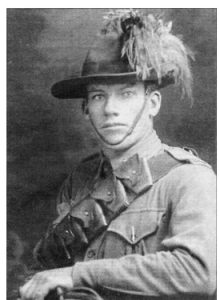

WILLIAM HENRY HAROLD KENNY DCM, (1887 – 1949)

MEDAILLE MILITARIE, MID 2ND LIGHT HORSE REGIMENT

|

The new arrivals scanned the hillside. Suddenly the scream of an incoing shell sent them flat against the rickety pier. The blast had scarcely subsided when a cool, calm voice came out of the darkness, “Come on lads, move on to the beach. The war’s waiting for you.” With that the NCO’s took charge and followed the direction of the military policeman as he waved them on.

The paddocks surrounding the family farm were his kingdom. He did his bit around the farm, feeding the chooks, collecting the eggs and gathering the wood. The shearing shed though, was an adventure all its own. He would spend hours watching the shearers shear the sheep with smooth simplicity. He would often sit alongside them as they enjoyed their smoko and liked them ruffling his hair as they went back to work. It was a big day for the boy when his father told him that he was old enough to start carrying the tar bucket for the men. The Kenny family, with eight children, enjoyed a strong bond. Unfortunately, two of the children, a girl and a boy, died at an early age. Billy was especially close to his mother, Mary. She idolised the boy and although she would never admit it to the others, he was her favourite. It was a huge affair as the family ushered in the new century. The boys were allowed the distinct privilege of toasting in the event with a small glass of beer. Young Billy scoured the newspapers. He read of the colonial horsemen’s fight against the infamous Boer commandos. Sword fights and attacks against the imaginary enemy filled every spare minute of his day. In 1908, he was a strapping six feet, one and a quarter inches tall when he presented himself for enlistment in the local militia unit, the 14th Light Horse Regiment. He was soon recognised as a good, solid soldier with a zest for learning the art of a light horseman. He rose steadily through to the rank of Sergeant. In 1913, he sought his discharge. “Don’t like losing blokes like you, Kenny,” his squadron commander said, “What do you intend to do?” “I don’t like leaving either sir, but we’re off to Queensland. The farm’s not doing too good and I’ve got to go where the work is.” William worked where he could find it. A competent farmer and bushman, he was able to turn his hand to almost anything. He developed a firm friendship with the local police constable, John Davidson. The pair had meet when kenny’s brother joined the force, some years before. “How would I go about joining:” Bill asked. “Just write a letter. I’ll give you a reference and having a brother in the force will go a long way,” the officer replied. Kenny grinned as he completed the questionnaire. Do you belong to a secret society? No. Can you ride a horse? Yes. Can you ride a bicycle? No. Can you swim? Yes. Are you in debt? No. Have you any illicit entanglements with females? No. Are you the parent of any illegitimate child? No. Kenny entered the Roma St Police Barracks as a trainee, on February 20, 1914. On his graduation nine weeks later, he was stationed next door at the Roma St Station. He’d been on the job a scant four months when war erupted. He loved the force but he also knew that he was a trained soldier. His mind made up, he sought leave and presented himself for enlistment in the AIF. He was allocated to A Sqn, 2nd Light Horse Regiment, which was to undergo initial training at the Enoggera Training Camp. The men were no sooner fitted with their uniforms and issued their mounts than they were ordered to prepare to sail as part of the first troop convoy, bound for Europe. Bill’s mother and sisters travelled to Brisbane to see him off. “Com on Mum, keep up a brave face, they say it will be over by Christmas,” he said. She couldn’t speak, all she could do was nod while she fought to hold back the tears. On the inside, Kenny was just as upset. As the convoy sailed across the vastness of the Indian Ocean, Bill and his mates continued their training. Map reading, physical training, weapons, lectures and first aid filled their days. The horses also need their constant attention, as they were the lifeblood of the regiment. A brief stop in South Africa and an even briefer stop in Colombo broke some of the boredom, so did the leisure hours. The troopers honed their skills on the sands of Egypts, instead of the plains of England. Cairo held a brief interest for Bill but the filth, smell and incessant badgering of the local merchants was not to his liking. Bill was summoned to his OC. “Yes, Kenny, we’re going to put some of that police training to use,” the major said. “The Military Mounted Police are a bit short-handed and with your background and experience you’d be a great help to them.” In April 1915, things began to stir. The infantry units of 1st Div took on a more intensive training program.

Day one of the campaign was utter chaos. The maps bore no resemblance to the surrounding countryside. Units were scattered and completely mixed up and the wounded were soon mounting up on the beach. The MP’s started work immediately to try and sort out some form of organisation on the beach. They signposted the tracks and briefed sub-unit commanders on the layout when coming ashore. Anything to get them off the beach. As the shells would slam into the beach area, the MP’s would quickly assume their duties once the immediate threat had passed and keep the continuous traffic moving. The hours were horrendous but the work satisfying as the constant build up of stores and men continued throughout the ensuing months. The MP’s were also tasked with the evacuation of prisoners of war back to the awaiting cages on the Lemnos and Mudros Islands for eventual movement back to Egypt. Bill was also chosen for a special duty – that of a personal bodyguard to the Commander of the Australian Forces – Lt-Gen William Birdwood. Kenny saw to his every need when it came to protection, especially outside the relative safety of his headquarters dugout. He was instrumental in the coordination of the close protection party, which was made up of troops from a number of allied armies. With the onset of the Aegean summer, the MP’s took on a new role. The cool, clear waters of Anzac Cove provided the soldiers with their only form of bathing and recreation. The sight of a closely packed group of soldiers frolicking in the sea was a tempting target for the Turkish guns, so a pass system was introduced. The troopers would check the passes and give any warnings as to daily threat that might challenge the bathers. One day, Kenny was going about his normal duties when suddenly he felt as though a horse had kicked him in the head. The burning sensation in his scalp was like a red-hot poker. When the medic ran to his aid, he discovered a sniper’s bullet had creased Kenny’s skull. “That was a close one mate,” the medic said as he bandaged the trooper’s head. The wound was painful but did not warrant Kenny’s evacuation from the peninsular, not that he would have gone anyway. He had proven himself to be a strong dependable soldier, who never shied away from the task. Mail call was always a welcomed time for Bill. As he sat on the ration box and read the letter, he suddenly looked up. “Bloody hell!” he screamed. “What’s wrong Bill, bad news?” his mate enquired. “Yeah, me sister’s joined up as a nurse,” Will explained. “What’s wrong with that, it’s pretty safe for them,” the digger answered. “Yeah, but it’s me mum, that’s two of us away now. She’ll be worried sick.” In late 1915, a special visitor arrived on Anzac. Lord Kitchener had come to inspect the situation at Gallipoli. His decision was simple – evacuation! The plan was developed. The Anzac forces would be extracted over a series of nights, under the noses of the enemy. Kenny and the other MP’s would play an instrumental part in the plan. They would continue to bring stores ashore by day to make it look like business as usual to the Turks, while at night they would man critical junction points, to ensure the silent, smooth movement of troops to the waiting barges tied up alongside the piers. As the Anzac forces sorted themselves out in Egypt, the strain of the preceding months took its toll on Bill Kenny. He was hospitalised later with a severe case of haemorrhoids. Following his release from hospital, Bill found himself posted to the 2nd Anzac HQ Police. He and other members of the unit would often patrol the streets of Cairo, keeping a check on the diggers. Kenny’s actions at Gallipoli had not gone unnoticed to his superiors either. He’d learnt that he had been Mentioned in Dispatches and in July 1916, he was informed that he had also been awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal and by the French, the Medaille Militaire. Extracts from the citation said it all. “For general good service and devotion to duty – was present at Anzac throughout the period first landing in April to evacuation in December and was never absent from duty a day – carrying out various police duties on piers and beaches frequently under shellfire — always in exemplary manner.” Bill was again hospitalised and following his release, he was temporarily assigned to the 1st Light Horse Training Regt. A few weeks after he was attached to the 14th Training Battalion. A dispatch was distributed to all units calling on members to be selected for the formation of the new Anzac Provost Corps. The dispatch stated that preference would be given to members holding either the Distinguished Conduct Medal or Military Medal. Bill was one of the first to apply and was granted selection. Then came the orders that he had been waiting for – embarkation to France with a promotion to lance corporal thrown in for good measure. He was to be attached to the 1st Anzac HQ. France was a whole new ball game. The allied forces had been slugging it out for nearly two years with the crack German units and the ground gained could only be measured in yards, not miles. Again the MP’s were up to the task. They controlled the vital supply routes, to ensure that the ammunition, food and water got through to where it could do the most good – with the blokes in the trenches. Bill survived the winter of 1916-17, said by many to be the worst in 50 years. Standing for long hours in knee-deep mud with snow and rain driving into his face, he manned the vital traffic points. He still pined for his family at home. In February 1917 he requested permission to return to Australia to visit his mother but was refused. He was given a choice – a spot of blighty leave or a trip to Paris. Although he had his heart set on home, he settled for England. The rest was like a tonic. He was able to write home and tell of the sights and sounds of London and the surrounding countryside but all the time he continued to tell his mother of his heartache at missing her and his sisters. He was unaware that his family feared for his well being. His sisters had written to Army HQ pleading for him to be sent home. They felt that his service at Gallipoli must count for something. They were genuinely concerned for their brother’s welfare. Although the Army was sympathetic to their concerns, they felt that they could not just send a man home because he was homesick. They were assured that he would be looked after and if their relative unit headquarters were at all concerned they would take care of the matter. So, with that, LCpl Kenny soldiered on. He picked up his second stripe at the end of March 1917. He was attached to the second Army Provost School jumping straight to Staff Sergeant. His promotion to warrant officer class two followed a scant three weeks later. Bill was now trained in the higher echelons of police work. He saw duty in Corps Headquarters where security was everything. He continued to provide the highest degree of service during the madcap days of April 1918, when the German counter attack all but captured Amiens and would have advanced all the way to the Channel, had it not been for the dogged defence from the Anzac Forces. He took another two-week break in London in July of that year. He was able to meet up with his sister and they had a grand time of it. As all good things must come to an end, he returned to France, just in time for the drive for the Rhine. He was shipped by train to Taranto and in a matter of days he was on a troopship bound for home. When the ship docked he ran down the gangway to the waiting arms of his family. He read of the armistice and enjoyed his leave. He was finally discharged from the AIF on January 24, 1919, and resumed duty with the police force a month later. Kenny married his sweetheart, Christina, at St Stephen’s Cathedral on October 27, 1919. The following year, the pair was posted to the Gilbert River Station about 400 km west of Tully, Queensland. He soon became a trusted member of the town community, displaying the fair and firm attitude to the town’s people that had carried him so well throughout the years. He received another Mentioned in Dispatches for his work in France. This was gazetted in August 1921. “Better late than never,” he thought to himself. In 1927, Kenny again received a favourable comment on his record, when he was instrumental in recovering a number of calves that had been stolen from the nearby Oakland Park Station. In 1932, Kenny was transferred to the Tewantin Station, this time as the Station Officer. A further transfer to a larger station at Cloncurry followed in 1934, where he sat his exams to become a first class sergeant of Police. A cream posting at Toowoomba followed in 1936. In November 1942, Kenny tried to effect the arrest of one Percy Richards. In the ensuing struggle, Kenny sustained a severe injury to his ankle in which a bone was fractured. Kenny was placed on sick leave but his condition didn’t improve. He was sent to Brisbane to front a Police Medical Board, which deemed him as unfit for further service. Bill Kenny retired from the police force after 29 years of service. Kenny presented himself for enlistment in the Army’s Volunteer Defence Corps on May 10, 1943 – he was nearly 56 years old at the time. Given the rank of sergeant, he attended an Infantry Section Leaders Course in July of that year. He got 48 per cent on his written exam, 52 per cent on his practical and 53 per cent on his oral. He was promoted to WO2 on November 8, 1943 and WO1 on March 17, 1944. As the war moved further away from Australia’s shores, the need for the VDC grew less. Bill Kenny was placed on the reserve list on August 1,1944. Kenny returned to his occupation as a market gardener and later became involved in the Boy Scout movement, rising to the position as District Commissioner. Stomach problems began to trouble Kenny soon after his release from the VDC. He visited the local doctor who conducted a series of tests. He was hospitalised and underwent some exploratory surgery. As he came out of the anaesthetic, he saw his wife sitting by his bedside. She displayed a cheerful attitude but the old soldier knew something was wrong. As the doctor entered the room he said, “G’day Bill, how are you feeling?” “Let’s cut the small talk, Doc, and get to the point,” Bill said. The doctor laid it on the line. “The news is not good Bill.” “What is it Doc, give it to me straight.” “It’s a tumour in the stomach – it’s as big as your fist.” “How long have I got?” “God knows,” the doctor replied. Bill fought on with the same dogged determination that had carried through his military service. He and Christina lived every day as if it were his last. His health took a turn for the worst in early 1949. His sister Elizabeth, who had served as the AIF nurse in WW1 and was now a leading figure in the fight against polio, rushed to his bedside from the US. They joked about the good old days on leave in London. He said how proud he was of her medical achievements and what she was doing for the polio victims. He fought on but the end was inevitable. The old copper fought his last fight on May 15, 1949. He lost. The RACMP will name the new building complex of 1 MP Coy at Lavarack Barracks after a prominent military policeman. The name they have chosen is William Kenny DCM, Medaille Militaire, MID. JUST SOLDIERS – ARMY NEWSPAPER

|

Kenny arrived at the unit and received his briefing. He found that the MP’s were the epitome of professionalism. Always correctly dressed and clear and firm in their directions as to what their duties would be from the outset. They were destined to be put ashore early in the piece and had to be ready to assume control of the beach area from the outset.

Kenny arrived at the unit and received his briefing. He found that the MP’s were the epitome of professionalism. Always correctly dressed and clear and firm in their directions as to what their duties would be from the outset. They were destined to be put ashore early in the piece and had to be ready to assume control of the beach area from the outset.